- Home

- Gregory Maguire

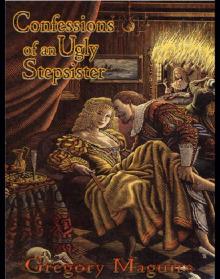

Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister

Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister Read online

Confessions

of an Ugly

Stepsister

GREGORY MAGUIRE

ILLUSTRATIONS BY BILL SANDERSON

For Andy Newman

CONTENTS

E-BOOK EXCLUSIVE EXTRA

Epigraph

PROLOGUE:

Stories Painted on Porcelain

1. THE OBSCURE CHILD

Marketplace

Stories Told Through Windows

Looking

Meadow

Sitting for Schoonmaker

Girl with Wildflowers

Half a Door

Van den Meer’s Household

2. THE IMP-RIDDLED HOUSE

The Small Room of Outside

Small Oils

The Masterpiece

Rue, Sage, Thyme, and Temper

Reception

Virginal

Simples

3. THE GIRL OF ASHES

Flowers for the Dead

Plague and Quarantine

The Nowhere Windmill

Invitations

A Fair Light on a Full Table

Wind and Tide

The Girl of Ashes

Finery

Spine and Chamber

Collapses

4. THE GALLERY OF GOD’S MISTAKES

Campaigns

The Gallery of God’s Mistakes

Cinderella

Van Stolk and van Antum

The Night Before the Ball

The Changeling

Small Magic

Tulip and Turnips

5. THE BALL

The Medici Ball

Clarissa of Aragon

Midnight

A Most Unholy Night

The Second Slipper

epilogue

Reader’s Group Guide

About the Author

Praise for . . .

Also by Gregory Maguire

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

E-BOOK EXCLUSIVE EXTRA

Cinderella, or, The Little Glass Slipper from Perrault’s Histories

Epigraph

If I could say to you, and make it stick,

A girl in a red hat, a woman in blue

Reading a letter, a lady weighing gold . . .

If I could say this to you so you saw,

And knew, and agreed that this is how it was

In a lost city across the sea of years,

I think we should be for one moment happy

In the great reckoning of those little rooms . . .

—Howard Nemerov, “Vermeer,”

from Trying Conclusions:

Old and New Poems

Stories Painted

on Porcelain

Hobbling home under a mackerel sky, I came upon a group of children. They were tossing their toys in the air, by turns telling a story and acting it too. A play about a pretty girl who was scorned by her two stepsisters. In distress, the child disguised herself to go to a ball. There, the great turnabout: She met a prince who adored her and romanced her. Her happiness eclipsed the plight of her stepsisters, whose ugliness was the cause of high merriment.

I listened without being observed, for the aged are often invisible to the young.

I thought: How like some ancient story this all sounds. Have these children overheard their grandparents revisiting some dusty gossip about me and my kin, and are the little ones turning it into a household tale of magic? Full of fanciful touches: glass slippers, a fairy godmother? Or are the children dressing themselves in some older gospel, which my family saga resembles only by accident?

In the lives of children, pumpkins can turn into coaches, mice and rats into human beings. When we grow up, we learn that it’s far more common for human beings to turn into rats.

Nothing in my childhood was charming. What fortune attended our lives was courtesy of jealousy, greed, and murder. And nothing in my childhood was charmed. Or not that I could see at the time. If magic was present, it moved under the skin of the world, beneath the ability of human eyes to catch sight of it.

Besides, what kind of magic is that, if it can’t be seen?

Maybe all gap-toothed crones recognize themselves in children at play. Still, in our time we girls rarely cavorted in the streets! Not hoydens, we!—more like grave novices at an abbey. I can conjure up a very apt proof. I can peer at it as if at a painting, through the rheumy apparatus of the mind . . .

. . . In a chamber, three girls, sisters of a sort, are bending over a crate. The lid has been set aside, and we are digging in the packing. The top layer is a scatter of pine boughs. Though they’ve traveled so far, the needles still give off a spice of China, where the shipment originated. We hiss and recoil—ughh! Dung-colored bugs, from somewhere along the Silk Route, have nested and multiplied while the ship trundled northward across the high road of the sea.

But the bugs don’t stop us. We’re hoping to find bulbs for planting, for even we girls have caught the fever. We’re eager for those oniony hearts that promise the tulip blossoms. Is this is the wrong crate? Under the needles, only a stack of heavy porcelain plates. Each one is wrapped in a coarse cloth, with more branches laid between. The top plate—the first one—hasn’t survived the trip intact. It has shattered in three.

We each take a part. How children love the broken thing! And a puzzle is for the piecing together, especially for the young, who still believe it can be done.

Adult hands begin to remove the rest of the valuable Ming dinnerware, as if in our impatience for the bulbs we girls have shattered the top plate. We wander aside, into the daylight—paint the daylight of childhood a creamy flaxen color—three girls at a window. The edges of the disk scrape chalkily as we join them. We think the picture on this plate tells a story, but its figures are obscure. Here the blue line is blurred, here it is sharp as a pig’s bristle. Is this a story of two people, or three, or four? We study the full effect.

Were I a painter, able to preserve a day of my life in oils and light, this is the picture I would paint: three thoughtful girls with a broken plate. Each piece telling part of a story. In truth, we were ordinary children, no calmer than most. A moment later, we were probably squabbling, sulking over the missing flower bulbs. Noisy as the little ones I observed today. But let me remember what I choose. Put two of the girls in shadow, where they belong, and let light spill over the third. Our tulip, our Clara.

Clara was the prettiest child, but was her life the prettiest tale?

Caspar listens to my recital, but my quavery voice has learned to speak bravely too late to change the story. Let him make of it what he will. Caspar knows how to coax the alphabet out of an inky quill. He can commit my tale to paper if he wants. Words haven’t been my particular strength. What did I see all my life but pictures?—and who ever taught the likes of me to write?

Now in these shriveled days, when light is not as full as it used to be, the luxury of imported china is long gone. We sip out of clay bowls, and when they crack we throw them on the back heap, to be buried by oak leaves. All green things brown. I hear the youthful story of our family played by children in the streets, and I come home muttering. Caspar reminds me that Clara, our Clara, our Cindergirl, is dead.

He says it to me kindly, requiring this old head to recall the now. But old heads are more supple at recalling the past.

There are one or two windows into those far-off days. You have seen them—the windows of canvas that painters work on so we can look through. Though I can’t paint it, I can see it in my heart: a square of linen that can remember an afternoon of relative happiness. Creamy flaxen light, the blue and ivory of porcelain. Girls believi

ng in the promise of blossoms.

It isn’t much, but it still makes me catch my breath. Bless the artists who saved these things for us. Don’t fault their memory or their choice of subject. Immortality is a chancy thing; it cannot be promised or earned. Perhaps it cannot even be identified for what it is. Indeed, were Cinderling to return from the dead, would she even recognize herself, in any portrait on a wall, in a figure painted on a plate, in any nursery game or fireside story?

I

THE OBSCURE CHILD

Marketplace

The wind being fierce and the tides unobliging, the ship from Harwich has a slow time of it. Timbers creak, sails snap as the vessel lurches up the brown river to the quay. It arrives later than expected, the bright finish to a cloudy afternoon. The travelers clamber out, eager for water to freshen their mouths. Among them are a strict-stemmed woman and two daughters.

The woman is bad-tempered because she’s terrified. The last of her coin has gone to pay the passage. For two days, only the charity of fellow travelers has kept her and her girls from hunger. If you can call it charity—a hard crust of bread, a rind of old cheese to gnaw. And then brought back up as gorge, thanks to the heaving sea. The mother has had to turn her face from it. Shame has a dreadful smell.

So mother and daughters stumble, taking a moment to find their footing on the quay. The sun rolls westward, the light falls lengthwise, the foreigners step into their shadows. The street is splotched with puddles from an earlier cloudburst.

The younger girl leads the older one. They are timid and eager. Are they stepping into a country of tales, wonders the younger girl. Is this new land a place where magic really happens? Not in cloaks of darkness as in England, but in light of day? How is this new world complected?

“Don’t gawk, Iris. Don’t lose yourself in fancy. And keep up,” says the woman. “It won’t do to arrive at Grandfather’s house after dark. He might bar himself against robbers and rogues, not daring to open the doors and shutters till morning. Ruth, move your lazy limbs for once. Grandfather’s house is beyond the marketplace, that much I remember being told. We’ll get nearer, we’ll ask.”

“Mama, Ruth is tired,” says the younger daughter, “she hasn’t eaten much nor slept well. We’re coming as fast as we can.”

“Don’t apologize, it wastes your breath. Just mend your ways and watch your tongue,” says the mother. “Do you think I don’t have enough on my mind?”

“Yes, of course,” agrees the younger daughter, by rote, “it’s just that Ruth—”

“You’re always gnawing the same bone. Let Ruth speak for herself if she wants to complain.”

But Ruth won’t speak for herself. So they move up the street, along a shallow incline, between step-gabled brick houses. The small windowpanes, still unshuttered at this hour, pick up a late-afternoon shine. The stoops are scrubbed, the streets swept of manure and leaves and dirt. A smell of afternoon baking lifts from hidden kitchen yards. It awakens both hunger and hope. “Pies grow on their roofs in this town,” the mother says. “That’ll mean a welcome for us at Grandfather’s. Surely. Surely. Now is the market this way?—for beyond that we’ll find his house—or that way?”

“Oh, the market,” says a croaky old dame, half hidden in the gloom of a doorway, “what you can buy there, and what you can sell!” The younger daughter screws herself around: Is this the voice of a wise woman, a fairy crone to help them?

“Tell me the way,” says the mother, peering.

“You tell your own way,” says the dame, and disappears. Nothing there but the shadow of her voice.

“Stingy with directions? Then stingy with charity too?” The mother squares her shoulders. “There’s a church steeple. The market must be nearby. Come.”

At the end of a lane the marketplace opens before them. The stalls are nested on the edges of a broad square, a church looming over one end and a government house opposite. Houses of prosperous people, shoulder to shoulder. All the buildings stand up straight—not like the slumped timber-framed cottage back in England, back home . . .

—the cottage now abandoned . . . abandoned in a storm of poundings at the shutters, of shouts: “A knife to your throat! You’ll swallow my sharp blade. Open up!”. . . Abandoned, as mother and daughters scrambled through a side window, a cudgel splintering the very door—

Screeeee—an airborne alarm. Seagulls make arabesques near the front of the church, being kept from the fish tables by a couple of tired, zealous dogs. The public space is cold from the ocean wind, but it is lit rosy and golden, from sun on brick and stone. Anything might happen here, thinks the younger girl. Anything! Even, maybe, something good.

The market: near the end of its day. Smelling of tired vegetables, strong fish, smoking embers, earth on the roots of parsnips and cabbages. The habit of hunger is a hard one to master. The girls gasp. They are ravenous.

Fish laid to serry like roofing tiles, glinting in their own oils. Gourds and marrows. Apples, golden, red, green. Tumbles of grapes, some already jellying in their split skins. Cheeses coated with bone-hard wax, or caught in webbing and dripping whitely—cats sprawl beneath like Ottoman pashas, open-mouthed. “Oh,” says the younger sister when the older one has stopped to gape at the abundance. “Mama, a throwaway scrap for us! There must be.”

The mother’s face draws even more closed than usual. “I won’t have us seen to be begging on our first afternoon here,” she hisses. “Iris, don’t show such hunger in your eyes. Your greed betrays you.”

“We haven’t eaten a real pasty since England, Mama! When are we going to eat again? Ever?”

“We saw few gestures of charity for us there, and I won’t ask for charity here,” says the mother. “We are gone from England, Iris, escaped with our lives. You’re hungry? Eat the air, drink the light. Food will follow. Hold your chin high and keep your pride.”

But Iris’s hunger—a new one for her—is for the look of things as much as for the taste of them. Ever since the sudden flight from England . . .

—running along the shadowed track, panting with pain in the chest, tumbling into a boat in the darkness—running, with the fear of hobgoblins at their heels. Imps, thwarties, grinning like demons, hungry to nip their ankles and sip their blood—

And what if an imp has secreted itself in the Harwich ship and follows like a skulking dog, to pester them in this new land all over again?

To keep from a panic, Iris says to herself: Look at how things are, look: there, there, there. . . . We are someplace new, someplace else, safer.

Ruth stops. She is older than Iris, a solid thing, already more than normal adult size, but simple. A pendulum of spit swings out and makes a tassel. Iris reaches and wipes Ruth’s mouth. Ruth has a set of shoulders that would grace an ox, but she doesn’t have an ox’s patience. Her brown eyes blink. She lunges toward the nearest rack of produce, a tray heaped with sun-spotted early pears.

“No, Ruth,” says the mother, and pulls her back.

Iris has a sudden notion of how she and her family must look, as stolid Englishers: Englishers in this European other-world, with its close, rich hills of architecture. The lumpy Fisher family, traipsing like oafs on a pilgrimage: —The spiky mother, Margarethe, tugging at her gigantic firstborn. —Ruth, heaving her lungs like a bellows, working up to a wail. —And Iris herself, gaunt and unlovely as a hermit, shrinking into herself as best she can.

The men of the market duck their heads to keep from watching a woman’s woes. The wives of the market, however, stare and don’t give any ground. No one offers a bruised apple or a smallish pear to calm Ruth or to make Margarethe’s plight easier. The market women tuck their hands in apron pockets to mind their small clutches of coins. There’s no habit of charity here, at least not for the ugly foreigner.

Strong Ruth is less pliant than usual. She nearly succeeds in breaking out of her mother’s grip. Margarethe, sorely tried, pitches her voice low. “Ruth! God’s mercy, that I’m harnessed to such a beast! Give way, yo

u willful thing, or I’ll beat you when we get to Grandfather’s. In a strange place, and no one to wipe your eyes then, for I’ll keep Iris from cozening you!”

Though slow, Ruth is a good daughter. Today, however, hunger rules her. She can’t break from Margarethe’s hold, but she kicks out and catches the corner of the rickety table on which the pears are piled. The vendor curses and dives, too late. The pears fall and roll in gimpy circles. Other women laugh, but uneasily, afraid that this big little girl will overturn their displays. “Mind your cow!” barks the vendor, scrabbling on her hands and knees.

Margarethe looses a hand toward Ruth’s face, but Ruth is twisting too fast. She backs up, away from the stall, against the front wall of a house. Margarethe’s slap falls weakly, more sound than sting. She hits Ruth again, harder. Ruth’s bleat mounts to a shriek, her head striking the bricks of the house.

A ground floor window in the house swings open, just next to Ruth. A treble voice rings out from within. It might be boy’s or girl’s. It’s a word of exclamation—perhaps the child has seen Ruth topple the pears? Heads turn in the marketplace, while Ruth twists toward the young voice and Margarethe grabs a firmer hold. Iris finds herself scooping forward, pear-ward, while all eyes are elsewhere. In another moment she too has swiveled her head to look.

She sees a girl, perhaps a dozen years old, maybe a little more? It’s hard to tell. The child is half hidden by a cloth hanging in the window, but a shaft of light catches her. The late afternoon light that gilds. The market stops cold at the sight of half the face of a girl in a starched collar, a smudge of fruit compote upon her cheek.

The girl has hair as fine as winter wheat; in the attention of the sun, it’s almost painful to look at. Though too old for such nonsense, she clutches something for comfort or play. Her narrowed eyes, when she peers about the curtain’s edge, are seen to be the blue of lapis lazuli or the strongest cornflower. Or like the old enamel that Iris saw once in a chapel ornament, its shine worn off prematurely. But the girl’s eyes are cautious, or maybe depthless, as if they’ve been torn from the inside out by tiny needles and pins.

Missing Sisters

Missing Sisters Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West

Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West After Alice

After Alice Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister

Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister Son of a Witch

Son of a Witch Matchless

Matchless The Next Queen of Heaven

The Next Queen of Heaven Leaping Beauty: And Other Animal Fairy Tales

Leaping Beauty: And Other Animal Fairy Tales Hiddensee: A Tale of the Once and Future Nutcracker

Hiddensee: A Tale of the Once and Future Nutcracker A Wild Winter Swan

A Wild Winter Swan Egg & Spoon

Egg & Spoon Out of Oz

Out of Oz Leaping Beauty

Leaping Beauty Hiddensee

Hiddensee The Wicked Years Complete Collection

The Wicked Years Complete Collection The Next Queen of Heaven: A Novel

The Next Queen of Heaven: A Novel