Missing Sisters

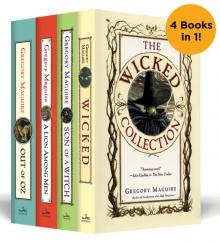

Missing Sisters Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West

Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West After Alice

After Alice Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister

Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister Son of a Witch

Son of a Witch Matchless

Matchless The Next Queen of Heaven

The Next Queen of Heaven Leaping Beauty: And Other Animal Fairy Tales

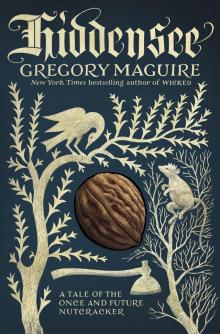

Leaping Beauty: And Other Animal Fairy Tales Hiddensee: A Tale of the Once and Future Nutcracker

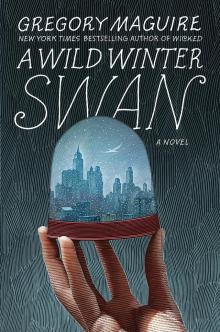

Hiddensee: A Tale of the Once and Future Nutcracker A Wild Winter Swan

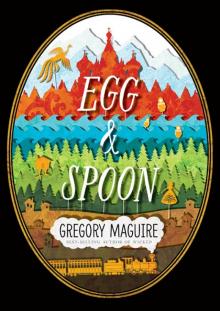

A Wild Winter Swan Egg & Spoon

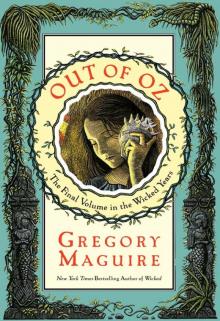

Egg & Spoon Out of Oz

Out of Oz Leaping Beauty

Leaping Beauty Hiddensee

Hiddensee The Wicked Years Complete Collection

The Wicked Years Complete Collection The Next Queen of Heaven: A Novel

The Next Queen of Heaven: A Novel