- Home

- Gregory Maguire

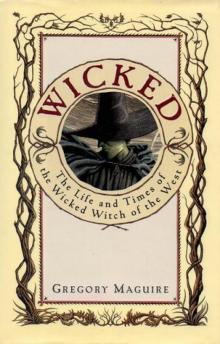

Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West Page 30

Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West Read online

Page 30

2

A week passed before Sarima said to Three, “Please tell our Auntie Guest that I’d like to see her tomorrow for elevenses in the Solar.” Sarima thought that Elphaba had had enough time now to get the measure of things. The suffering green woman was in some sort of slow-motion thrall, or fit. She moved jerkily, stalking about the courtyard, or stamping in to meals as if trying to poke holes in the flooring with her heels. Her elbows were always bent at right angles, and her hands clenched and unclenched themselves.

Sarima felt stronger than ever, which wasn’t very. It did her some good to have a contemporary around, however thwarted she might be. The sisters disapproved of Sarima’s cordiality, but the higher mountain passes were already closed for the winter, and you just couldn’t send a stranger packing into the treacherous valleys. The sisters conferred in their parlor, as they busied themselves knitting hateful gray potholders for the undeserving poor at Lurlinemas. She’s sick, they said; she’s inert, unfinished (even more than they were, was the unspoken corollary, an immensely gratifying notion); she’s damned. And is that fat balloon of a boy her son, or a child slave, or is he one of her familiars? Behind Sarima’s back they called the woman living in the cobbleshed Auntie Witch, echoing the old legends of Kumbricia, which were viler—and more persistent—in the Kells than elsewhere in Oz.

It was Manek, Sarima’s middle child, who was the most curious. One morning, as the boys all stood on a battlement pissing over the side (a game poor Nor had to pretend no interest in), Manek said, “What if we peed on Auntie? Would she scream?”

“She’d turn you into a toad,” said Liir.

“No, I mean would it hurt her? She looks like water gives her the aches and shakes. Does she even drink it? Or does it make her insides hurt?”

Liir, not an especially observant child, said, “I think she doesn’t drink it. Sometimes she washes things, but she uses sticks and brushes. We better not pee on her.”

“And what does she do with all those bees and the monkey? Are they magic?”

“Yeah,” said Liir.

“What kind of magic?”

“I don’t know.” They stepped away from the dizzying drop and Nor came running up. “I have a magic straw,” she said, holding up a brown bristle. “From the Witch’s broom.”

“Is the broom magic?” said Manek to Liir.

“Yes. It can sweep the floor real fast.”

“Can it talk? Is it enchanted? What does it say?”

They got more interested, and Liir bloomed and blushed under their curiosity. “I can’t tell. It’s a secret.”

“Is it still a secret if we push you off the tower?”

Liir considered. “What do you mean?”

“Will you tell us or we’ll do it.”

“Don’t push me off the tower, you oafs.”

“If the broom is magic it’ll come flying by and save you. Besides, you’re so fat you’d probably bounce.”

Irji and Nor laughed at that, despite themselves. It made a very funny picture in their minds.

“We only want to know what secrets the broom says to you,” said Manek with a big smile. “So tell us. Or we’ll push you off.”

“You’re not being nice, he’s company,” said Nor. “Come on, let’s go find some mice in the pantry and make friends.”

“In a minute. Let’s push Liir off the roof first.”

“No,” said Nor, beginning to cry. “You boys are so mean. Are you sure that broom is magic, Liir?”

But Liir by now didn’t want to say any more.

Manek tossed a pebble off the roof and it seemed a very long time before the ping of impact.

Liir’s face had, in a matter of moments, developed deep black pockets under the eyes. He held his hands down by his sides like a traitor at a court martial. “The Witch’ll be so mad at you that she will hate you,” Liir said.

“I don’t think so,” said Manek, taking a step forward. “She won’t care. She likes the monkey more than she likes you. She won’t even notice if you’re dead.”

Liir gasped for air. Although he had just peed, the front of his baggy trousers turned dark with wet. “Look, Irji,” said Manek, and his older brother looked. “He’s not even very good at being alive is he? It’s not like it would be much of a loss. Come on, Liir, tell me. What did the damned broom say to you?”

Liir’s upper torso was going in and out like a bellows. He whispered, “The broom told me—that—that—you’re all going to die!”

“Oh, is that all,” said Manek. “We already knew that. Everybody dies. We knew that already.”

“You did?” said Liir, who hadn’t.

“Come on,” Irji said, “come on, let’s catch some mice in the pantry and we can cut off their tails and use Nor’s magic straw to prick their eyes.”

“No!” said Nor, but Irji had swiped the straw from her. Manek and Irji went clattering, loose-limbed as marionettes, along the parapet

and down the stairs. With a huge, aggrieved sigh, Liir composed himself and adjusted his clothes, and followed them like a condemned dwarf laborer in the emerald mines. Nor stayed behind, her arms folded defiantly, her chin working with frustration. Then she spit over the edge and felt better, and chased after the boys.

At midmorning, Six showed the guest into the Solar. With a smirk behind Auntie’s back, she deposited a tray of cruel little biscuits, hard as slate, on a table covered with a carpet gone brown and patternless. Sarima, having made her way through what she could of her daily spiritual ablutions, felt ready.

“You’ve been here a week and it’s likely to be longer,” said Sarima, allowing Six to pour out some gallroot coffee before dismissing her. “The trail north is snowed in by now, and there’s not a safe haven between here and the plains. The winters are hard in the mountains, and while we can make do with our stores and our own company, we treasure a change. Milk? I do not know exactly what you had—intended. Once you had visited us sufficiently, I mean.”

“There are rumors of caves in these Kells,” Elphaba said, almost more to herself than to Sarima. “I lived for some years at the Cloister of Saint Glinda in the Shale Shallows, outside of the Emerald City. Dignitaries would visit, and while we were often under a vow of silence, nonetheless people would talk of what they knew. Monastic cells. I had thought, when I was done here, that I might take myself to a cave and—and—”

“And set up housekeeping,” said Sarima, as if this were as usual as marrying and bearing babies. “Some do it, I know. There’s an old hermit on the western slope of Broken Bottle—that’s a peak nearby—they say he’s been there for some years, and has reverted to a more primitive moment of nature. Of his nature, I mean.”

“A life without words,” Elphie said, looking in her coffee and not drinking it.

“They say this hermit has forgotten about personal hygiene,” said Sarima, “which, given how the boys smell when they go unwashed for a couple of weeks, strikes me as nature’s defense against marauding beasts.”

“I didn’t expect to be here for a long time,” Elphie said, twisting her head on her neck like a parrot and looking at Sarima in an odd way. Oh, beware, thought Sarima carefully, though she tended to like this guest: Beware, she’s taking the direction of the discussion into her own hands. This won’t do. But the guest went on: “I had thought that I would have a night or two, maybe three, and could find myself a hidey-hole before winter set in. I was working on the wrong calendar, I was thinking of how, and when, winter came to Shiz and the Emerald City. But you’re six weeks ahead here.”

“Ahead in the autumn and behind in the spring, alas,” said Sarima. She took her feet off her hassock and placed them on the floor, flatly, to indicate seriousness. “Now, my new friend, there are some things I need to say to you.”

“I have things too,” Elphie said, but Sarima went on this time.

“You will think me an unpolished person, and you are right of course. Oh, when I was selected to be a child bride, a good gover

ness was hired from Gillikin to teach me and my sisters how to use verbs and pronouns and salad forks. And lately I have begun to master reading. But most of what I picked up about polite behavior was from what Fiyero was good enough to instruct me in when he returned from his education. No doubt I make social mistakes. You have every right to snigger behind my back.”

“I am not given to sniggering,” snapped Elphaba.

“As it may be. But I still have opinions, and I’m observant even if unschooled. Despite my sheltered life, married at the age of seven as you may know, raised and reared behind castle curtain walls. I trust my own sense of things and won’t be dissuaded. So let me continue,” she said, as Elphaba tried to interrupt. “There is plenty of time and the sun is nice in here, isn’t it? My little hideaway.

“It seems to me that you have come here to—shall we say—relieve yourself of some sad business or other. You have the look about you. Don’t be startled, my dear, if there’s a look I do recognize, it’s the look of someone carrying a burden. Remember, I listen to my sisters, year in and year out, as they graciously share with me all the ways they hate me, and why.” She smiled, amused at her own wit. “You want to throw down your burden, throw it down at my feet, or across my shoulders. You want perhaps to weep a little, to say good-bye, and then to leave. And when you leave here you will walk right out of the world.”

“I will do no such thing,” said Elphie.

“You will indeed, even if you don’t know it. You will have nothing left to tie you to the world. But I know my own limits, Auntie Guest, and I know what you’re here for. You told me. You told me in the hall, you said you felt you were responsible for Fiyero’s death—”

“I—”

“Don’t. Just don’t. This is my home, I am a nominal Dowager Princess of Duckshit, but I have a right to hear and I have a right not to hear. Even to make a traveler feel better.”

“I—”

“Don’t.”

“But I don’t want to burden you, Sarima, I want to unburden you with the truth—if you permit me, you are the larger, the lighter; forgiveness blesses the donor as well as the receiver.”

“I’ll overlook that remark about my being the larger,” said Sarima. “But I still have the right to choose. And I think you wish me ill. You wish me ill and you don’t even know it. You want to punish me for something. Maybe for not being a good enough wife to Fiyero. You wish me ill and you fool yourself to think it’s some therapeutic course of tablets.”

“Do you know how he died, at least?” said Elphaba.

“I know it was a violent action, I know his body was never found, I know it was in a little love nest,” said Sarima, for a minute losing her resolve. “I don’t care to know who it was exactly, but I have heard enough about that vile Sir Chuffrey to have my strong opin—”

“Sir Chuffrey!”

“I said no. I said no more. Now I have an offer to make of you, Auntie, if you will have it. You and the boy may move into the southeast tower if you like. There are a couple of big round rooms with high ceilings, and good light, and you’ll be out of that drafty cobbleshed, and warmer. You’ll have your own staircase to come and go into the main hall, and you won’t bother the girls and they won’t trouble you. You can’t stay in that cobbleshed all winter. The boy has been looking pale and blubbery, I think he’s always cold. You’re there on the condition, I’m afraid, that you accept my firmest word on these matters. I don’t care to discuss my husband or the affairs of his death with you.”

Elphaba looked horror-struck, and beaten. “I have no choice but to accept,” she said, “at least for the time being. But I warn you, I intend to befriend you so thoroughly that you will change your mind. And I do think you need to hear things, you need to talk about them, as I do—and I can’t leave into the wilderness until I have your solemn promise of—”

“Enough!” said Sarima. “Call the porter from the gatehouse and have him bring your luggage to the tower. Come, I’ll show you. You haven’t touched your coffee.” She stood. For an awkward moment there was respect and suspicion, in equal measure, simmering on the carpet like the dust in the sunbeams. “Come,” Sarima said, more softly, “at the very least you need to be warm. You must be able to say that much of us country mice here at Kiamo Ko.”

3

As far as Elphaba was concerned, it was a witch’s room, and she reveled in it. Like all good witch’s rooms in children’s stories, it was a room with bowed walls, following the essential form of a tower. It had one broad window that, since it faced east, away from the wind, could be unbarred and opened without blowing everyone and everything out into the snowy valleys. Beyond, the Great Kells were a rank of sentinels, purple-black when the winter sun rose over them, draining into blue-white screens as the sun moved overhead, and going golden and ruddy in the late afternoon. There were sometimes rumbling collapses of ice and scree.

The winter gripped the house. Elphaba learned soon enough to stay put unless she was sure another room had a warmer fire. And except for Sarima, she didn’t care for the other human company the house afforded. Sarima lived in the west wing, with the children: the boys Irji and Manek, the girl Nor. Sarima’s five sisters lived in the east wing—they were called numbers Two through Six, and if they had ever had other names they had withered away from disuse. By right of their unmarriageability, the sisters claimed the best rooms in the place, although Sarima had the Solar. Where Liir curled up to sleep Elphaba did not know, but he reappeared every morning to change the rags at the bottom of the crows’ perch. He brought her cocoa, too.

Lurlinemas drew near, and out came some tired decorations from which the gilt had all but vanished. The children spent a whole day tying baubles and toys to the archways, making the grown-ups bump their heads and curse. Manek and Irji took a saw and without permission went beyond the castle walls to claim some boughs of spruce and sprigs of holly. Nor stayed behind and painted scenes of happy life in the castle on sheets of paper that she and Liir had found in Auntie Witch’s room. Liir said he couldn’t draw, so he wandered off and disappeared, perhaps to stay clear of Manek and Irji. The house fell still until there was a flurry of copper pans thrown about the kitchen. Nor went running to see, and Liir arrived from some hiding cubby to look too.

It was Chistery. The monkey was having a fit, and all the sisters, baking gingerbread, were throwing gobbets of batter at him, trying to knock him off the wheel that hung, noisy with swinging utensils, above the worktable.

“How’d he get in here?” said Nor.

“Get him out, Liir, call him!” said Two. But Liir had no more authority over Chistery than they did. The monkey flew to the top of a wardrobe, then to a huge dried goods canister, and he pulled open a drawer and found a precious store of raisins, which he stuffed in his mouth. Six said, “Go get the ladder from the hall, you two, and bring it here,” but when they had, Chistery was back on the wheel, making it whirl and clatter like a roundabout at a carnival.

Four put a lump of mashed melon in a bowl. Five and Three took off their aprons, ready to rush him when he came down. Chistery was still eyeing the fruit when the door smacked open against the wall and Elphaba came lolloping in. “All this commotion, how can you hear yourselves think?” she cried, and then took in the sight of Chistery, suddenly abject and remorseful, and of the sisters, poised to ensnare him in their floury aprons.

“What the hell is this?” she said.

“No need to yell,” said Two sulkily, quietly, but they put down their aprons.

“I mean, what is this? What is really going on here? You all look like Killyjoy, with blood lust in your faces! You’re white with rage at this poor beast!”

“I think it’s not rage, it’s flour,” said Five, which made them giggle.

“You filthy savages,” said Elphie. “Chistery come here, come down here. Right now. You women deserve to be unmarried, so you don’t bring any little savage creepy children into the world. Don’t you ever lay a hand on this monkey, do

you hear me? And how did he get out of my room anyway? I was in the Solar with your sister.”

“Oh,” said Nor, remembering, “oh, Auntie, I’m sorry. It was us.”

“You?” She turned and looked at Nor as if for the first time, and Nor didn’t like it much. She shrank back against the door of the cold cellar. “What were you skulking about in my room for?” said Elphie.

“Some paper,” said Nor faintly, and in a desperate, all-or-nothing gamble, said, “I made some paintings for everybody, do you want to see, come here.”

Chistery in her arms, Elphaba followed them into the drafty hall, where the wind under the front door was making the papers flutter against the carved stone. The sisters came too, a safe distance behind.

Elphie got very quiet. “This is my paper,” she said. “I didn’t say you could use it. Look, it has words on the back. Do you know what words are?”

“Of course I do, do you think I am slow?” responded Nor sassily.

“You leave my papers alone,” said Elphaba. She and Chistery then flew up the steps, and the door to the tower slammed behind them.

“Who wants to help roll out the gingerbread?” said Two, relieved that skulls hadn’t been knocked together. “And this hall looks very pretty, chickadees, I’m sure Preenella and Lurline will be impressed tonight.” The children went back into the kitchen and made gingerbread people, and crows, and monkeys, and dogs, but they couldn’t do bees, they were too small. When Irji and Manek came in, dumping snowy greens on the slate floor, they helped at the gingerbread shapes too, but they made naughty shapes that they wouldn’t show the younger children, and they kept gobbling up the raw dough and laughing hysterically at it, which made everyone else testy.

Missing Sisters

Missing Sisters Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West

Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West After Alice

After Alice Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister

Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister Son of a Witch

Son of a Witch Matchless

Matchless The Next Queen of Heaven

The Next Queen of Heaven Leaping Beauty: And Other Animal Fairy Tales

Leaping Beauty: And Other Animal Fairy Tales Hiddensee: A Tale of the Once and Future Nutcracker

Hiddensee: A Tale of the Once and Future Nutcracker A Wild Winter Swan

A Wild Winter Swan Egg & Spoon

Egg & Spoon Out of Oz

Out of Oz Leaping Beauty

Leaping Beauty Hiddensee

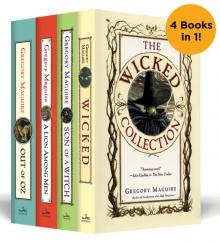

Hiddensee The Wicked Years Complete Collection

The Wicked Years Complete Collection The Next Queen of Heaven: A Novel

The Next Queen of Heaven: A Novel