- Home

- Gregory Maguire

The Wicked Years Complete Collection Page 5

The Wicked Years Complete Collection Read online

Page 5

She bundled up her breasts at last, reluctantly. Elphaba squawked to be let loose, and without so much as flinching the visitor unbuckled her and swept her in the air and caught her again. The child crowed with surprise, even delight, and Turtle Heart repeated the trick. Melena took advantage of his concentration on the brat to scoop up the uneaten minnow from the dirt and rinse it off. She plopped it among the eggs and mashed tar root, hoping that Elphaba would not suddenly learn to speak and embarrass her. It would be just like the child to do that.

But Elphaba was too charmed by this man to fuss or complain. She didn’t even whine when Turtle Heart finally came to the bench and sat to eat. She crawled between his sleek, hairless calves (for he had shucked off his leggings) and she moaned some private tune with a satisfied smirk on her face. Melena found herself jealous of a female not yet two years old. She wouldn’t have minded sitting on the ground between Turtle Heart’s legs.

“I’ve never met a Quadling before,” she said, too loudly, too brightly. The months of solitude had made her forget her manners. “My family would never have Quadlings in to dine—not that there were many, or even any for all I know, in the farmlands around my family’s estate. The stories make out that Quadlings were sneaky and incapable of telling the truth.”

“How can a Quadling to answer such a charge if a Quadling is given always to lie?” He smiled at her.

She melted like butter on warm bread. “I’ll believe anything you say.”

He told her of the life in the outreaches of Ovvels, the houses rotting gently into the swamp, the harvest of snails and murkweed, the customs of communal living and ancestor worship. “So you believe your ancestors are with you?” she prodded. “I don’t mean to be nosy but I’ve become interested in religion despite myself.”

“Does Lady to believe ancestors are with her?”

She could hardly focus on the question, so bright were his eyes, and so wonderful it was to be called Lady. Her shoulders straightened. “My immediate ancestors couldn’t be farther away,” she admitted. “I mean my parents—they’re still living, but so uninteresting to me they might as well be dead.”

“When dead they may to visit Lady often.”

“They are not welcome. Go away.” She laughed, shooing. “You mean ghosts? They’d better not. That’s what I’d call the worst of both worlds—if there is an Other Land.”

“There is an otherworld,” he said with certainty.

She felt chilled. She scooped Elphaba up and hugged her tightly. Elphaba sagged as if boneless in her arms, neither fussing nor returning the hug, just falling limp from the novelty of being touched. “Are you a seer?” said Melena.

“Turtle Heart to blow glass,” he said. He seemed to mean that as an answer.

Melena was suddenly reminded of the dreams she used to have, of exotic places she knew she was too dull to invent. “Married to a minister, and I don’t know that I believe in an otherworld,” she admitted. She hadn’t meant to say that she was married, although she supposed the child implicated her.

But Turtle Heart had finished talking. He put down his plate (he had left the minnow) and he took from his satchels a small pot, a pipe, and some sacks of sand and soda ash and lime and other minerals. “Might Turtle Heart to thank Lady for her welcome?” he asked; she nodded.

He built up the kitchen fire and sorted and mixed his ingredients, and arranged utensils, and cleaned the bowl of his pipe with a special rag folded in its own pouch. Elphaba sat clumplike, her green hands on her green toes, curiosity on her sharp pinched face.

Melena had never seen glass blown, just as she had never seen paper made, cloth woven, or logs hewn from tree trunks. It seemed as marvelous to her as the local stories of the traveling clock that had hexed her husband into the professional paralysis from which he still hadn’t quite escaped—though he tried.

Turtle Heart hummed a note through his nose or the pipe as he blew an irregular bulb of hot greenish ice. It steamed and hissed in the air. He knew what to do with it; he was a wizard of glass; Melena had to hold Elphaba back to keep her from burning her hands as she reached for it.

In what seemed like no time at all, in what felt like magic, the glass had gone from being semiliquid and abstract to a hardening, cooling reality.

It was a smooth, impure circle, like a slightly oblong plate. All the while Turtle Heart worked with it, Melena thought of her own character, going from youthful ether to hardening shell, transparently empty. Breakable, too. But before she could lose herself in remorse, Turtle Heart took her two hands and passed them near, but not touching, the flat surface of the glass.

“Lady to talk with ancestors,” he said. But she would not struggle to connect with old boring dead people in the Other Land, not when his huge hands covered hers. She breathed through her nose to suppress the smell of breakfast in an unwashed mouth (fruit and one glass of wine, or was it two?). She thought she might well faint.

“Look in glass,” he urged her. She could only look at his neck and his raspberry-honey-colored chin.

He looked for her. Elphaba came and steadied herself with a small hand on his knee and peered in, too.

“Husband is near,” said Turtle Heart. Was this prophecy through a glass dish or was he asking her a question? But he went on: “Husband is traveling on a donkey and to bring elderly woman to visit you. Is ancestor to visit?”

“Is old nursemaid, probably,” Melena said. She was sloping downward into his crippled syntax, in unabashed sympathy. “Can you really to see that in there?”

He nodded. Elphaba nodded too, but at what?

“How much time do we have before he gets here?” she asked.

“Till this evening.”

They did not speak another word until sunset. They banked the fire and hooked Elphaba to a harness, and sat her down in front of the cooling glass, which they hung on a string like a lens or a mirror. It seemed to mesmerize and calm her; she did not even gnaw absentmindedly at her wrists or toes. They left the door to the cottage open so that, from time to time, they could peer out from the bed to check on the child who, in the glare of a sunny day, would not be able to focus her eyes to see in the house shadows, and who anyway never turned to look. Turtle Heart was unbearably beautiful. Melena dragon-snaked with him, covered him with her mouth, poured him in her hands, heated and cooled and shaped his luminosity. He filled her emptiness.

They were washed, and dressed, with supper mostly made, when the donkey brayed a half mile down the lake. Melena blushed. Turtle Heart was back at the pipe, blowing again. Elphaba turned and looked in the direction of the donkey’s serrated statement. Her lips, which always looked almost black against the new-apple color of her skin, twisted tight, chewed against each other. She bit her lower lip as if thinking, but she did not bleed; she had learned to manage the teeth somewhat, through trial and error. She put her hand on the shining disc. The glass circlet caught the last blue of the sky, until it looked like a magic mirror showing nothing but silver-cold water within.

Geographies of the Seen and the Unseen

All the way from Stonespar End, where Frex met her coach, Nanny complained. Lumbago, weak kidneys, fallen arches, aching gums, sore haunches. Frex wanted to say, And how about your swollen ego? Though he had been out of circulation for a while, he knew such a remark would be rude. Nanny flounced and petted herself, clinging determinedly to her seat until they arrived at the lodge near Rush Margins.

Melena greeted Frex with affecting shyness. “My breastplate, my backbone,” she murmured. She was slender after a hard winter, her cheekbones more prominent. Her skin looked scoured as if by an artist’s scratch brush—but she had always had the look of an etching-in-the-flesh. She was usually bold with her kisses and he found her reticence alarming until he realized there was a stranger in the shadows. Then, after introductions, Nanny and Melena fussed to get a meal on the table, and Frex put out some oats for the sorry nag who had to pull the carriage. When this was done he went to sit in the spr

ing evening light and to meet his daughter again.

Elphaba was cautious around him. He found in his pouch a trinket he’d whittled for her, a little sparrow with a cunning beak and upraised wings. “Look, Fabala,” he whispered (Melena hated the derivative, so he used it: it was his and Elphaba’s private bond, the father-daughter pact against the world). “Look what I found in the forest. A little maplewood bird.”

The child took the thing in her hands. She touched it softly, and put its head in her mouth. Frex steeled himself to hear the inevitable splintering, and to hold back his sigh of disappointment. But Elphaba did not bite. She sucked the head and looked at it again. Wet, it had greater life.

“You like it,” Frex said.

She nodded, and began to feel its wings. Now that she was distracted, Frex could draw her between his knees. He nuzzled his crinkly-bearded chin into her hair—she smelled like soap and wood smoke, and the char on toast, a good healthy smell—and he closed his eyes. It was good to be home.

He had spent the winter in an abandoned shepherd’s hut on the windward slope of Griffon’s Head. Praying and fasting, moving deeper inside and then further outside himself. And why not? At home, he had felt the scorn of the people of the whole claustrophobic valley of Illswater; they had connected the Time Dragon’s slanderous story of a corrupt minister with the arrival of a deformed child. They had drawn their own conclusions. They avoided his chapel services. So a sort of hermit’s life, at least in small intervals, had seemed both penance and preparation for something else, something next—but what?

He knew this life wasn’t what Melena had originally expected, marrying him. With his bloodlines, Frex had looked primed for an elevation to proctor or even, eventually, bishop. He had imagined the happiness Melena would have as a society dame, presiding over feast day dinners and charity balls and episcopal teas. Instead—he could see her in the firelight, grating a last, limp winter carrot onto a pan of fish—here she wasted away, a partner in a difficult marriage on a cold, shadowy lakeshore. Frex had a notion that she wasn’t sorry to see him go off from time to time, so that she could be glad to see him come back.

As he ruminated, his beard tickled Elphaba’s neck, and she snapped the wings off her wooden sparrow. She sucked on it like a whistle. Twisting away from him, she ran to a glass lens hanging from the projecting eave, and swatted at it.

“Don’t, you’ll break that!” said her father.

“She cannot to break that.” The traveler, the Quadling, came from the sink where he had been washing up.

“She just turned her toy into a cripple,” Frex said, pointing at the ruined birdling.

“She is herself pleased at the half things,” Turtle Heart said. “I think. The little girl to play with the broken pieces better.”

Frex didn’t quite get it, but nodded. He knew that months away from the human voice made him clumsy at first. The boy from the inn, who had climbed Griffon’s Head to deliver Nanny’s request to be picked up at Stonespar End, had obviously thought Frex a wild man, grunting and unkempt. Frex had had to quote a little of the Oziad to indicate some sort of humanity—“Land of green abandon, land of endless leaf”—it was all that would come to him.

“Why can’t she break it?” asked Frex.

“Because I do not to make it to be broken,” answered Turtle Heart. But he smiled at Frex, not aggressively. And Elphaba wandered around with the shiny glass as if it were a toy, catching shadows, reflections, lights on its imperfect surface, almost as if she were playing.

“Where are you going?” asked Frex, just as Turtle Heart was saying, “Where are you from?”

“I’m a Munchkinlander,” said Frex.

“I to think all Munchkins to be shorter than I or you.”

“The peasants, the farmers, yes,” Frex said, “but anyone with bloodlines worth tracing married into height somewhere along the way. And you? You’re from Quadling Country.”

“Yes,” said the Quadling. His reddish hair had been washed and was drying into an airy nimbus. Frex was glad to see Melena so generous as to offer a passerby water to bathe in. Perhaps she was adjusting to country life after all. Because, mercy, a Quadling ranked about as low on the social ladder as it was possible to get and still be human.

“But I to understand,” said the Quadling. “Ovvels is a small world. Until I to leave, I am not to know of hills, one beyond the other and from the spiny backbones a world so wide around. The blurry far away to hurt my eyes, for I cannot to make it seen. Please sir to describe the world you know.”

Frex picked up a stick. In the soil he drew an egg on its side. “What they taught me in lessons,” he said. “Inside the circle is Oz. Make an X”—he did so, through the oval—“and roughly speaking, you have a pie in four sections. The top is Gillikin. Full of cities and universities and theatres, civilized life, they say. And industry.” He moved clockwise. “East, is Munchkinland, where we are now. Farmland, the bread basket of Oz, except down in the mountainous south—these strokes, in the district of Wend Hardings, are the hills you’re climbing.” He bumped and squiggled. “Directly south of the center of Oz is Quadling Country. Badlands, I’m told—marshy, useless, infested with bugs and feverish airs.” Turtle Heart looked puzzled at this, but nodded. “Then west, what they call Winkie Country. Don’t know much about that except it’s dry and unpopulated.”

“And around?” said Turtle Heart.

“Sandstone deserts north and west, fleckstone desert east and south. They used to say the desert sands were deadly poison; that’s just standard propaganda. Keeps invaders from Ev and Quox from trying to get in. Munchkinland is rich and desirable farming territory, and Gillikin’s not bad either. In the Glikkus, up here”—he scratched lines in the northeast, on the border between Gillikin and Munchkinland—“are the emerald mines and the famous Glikkus canals. I gather there’s a dispute whether the Glikkus is Munchkinlander or Gillikinese, but I have no opinion on that.”

Turtle Heart moved his hands over the drawing in the dirt, flexing his palms, as if he were reading the map from above. “But here?” he said. “What is here?”

Frex wondered if he meant the air above Oz. “The realm of the Unnamed God?” he said. “The Other Land? Are you a unionist?”

“Turtle Heart is glassblower,” said Turtle Heart.

“I mean religiously.”

Turtle Heart bowed his head and didn’t meet Frex’s eye. “Turtle Heart is not to know what name to call this.”

“I don’t know about Quadlings,” said Frex, warming to a possible convert. “But Gillikinese and Munchkinlanders are largely unionist. Since Lurlinist paganism went out. For centuries, there have been unionist shrines and chapels all over Oz. Are there none in Quadling Country?”

“Turtle Heart does not to recognize what is this,” he said.

“And now respectable unionists are going in droves over to the pleasure faith,” said Frex, snorting, “or even tiktokism, which hardly even qualifies as a religion. To the ignorant everything is spectacle these days. The ancient unionist monks and maunts knew their place in the universe—acknowledging the life source too sublime to be named—and now we sniff up the skirts of every musty magician who comes along. Hedonists, anarchists, solipsists! Individual freedom and amusement is all! As if sorcery had any moral component! Charms, alley magic, industrial-strength sound and light displays, fake shape-changers! Charlatans, nabobs of necromancy, chemical and herbal wisdoms, humbug hedonists! Selling their bog recipes and crone aphorisms and schoolboy spells! It makes me sick.”

Turtle Heart said, “Shall Turtle Heart to bring you water, shall Turtle Heart to lie you down?” He put fingers soft as calfskin on the side of Frex’s neck. Frex shivered and realized he had been shouting. Nanny and Melena were standing in the doorway with the pan of fish, silent.

“It’s a figure of speech, I’m not sick,” he said, but he was touched at the concern the foreigner had shown. “I think we’ll eat.”

And they did. Elphaba ign

ored her food except to prod the eyes out of the baked fish and to try to fit them onto her wingless bird. Nanny grumbled good-naturedly about the wind off the lake, her chills, her backbone, her digestion. Her gas was apparent from more than a few feet away and Frex moved, as discreetly as possible, to be upwind. He found himself sitting next to the Quadling on the bench.

“So is all that clear to you?” Frex pointed a fork at the map of Oz.

“Is Emerald City to be where?” said the Quadling, fish bones poking out from between his lips.

“Dead center,” Frex said.

“And there is Ozma,” said Turtle Heart.

“Ozma, the ordained Queen of Oz, or so they say,” Frex said, “though the Unnamed God must be ruler of all, in our hearts.”

“How can unnamed creature to rule—” began Turtle Heart.

“No theology at dinner,” sang out Melena, “that’s a house rule dating from the start of our marriage, Turtle Heart, and we obey it.”

“Besides, I still harbor a devotion to Lurline.” Nanny made a face in Frex’s direction. “Old folks like me are allowed to. Do you know about Lurline, stranger?”

Turtle Heart shook his head.

“If we have no theology then we surely have no arrant pagan nonsense—” began Frex, but Nanny, being a guest and invoking a touch of deafness when it suited her, plowed on.

“Lurline is the Fairy Queen who flew over the sandy wastes, and spotted the green and lovely land of Oz below. She left her daughter Ozma to rule the country in her absence and she promised to return to Oz in its darkest hour.”

“Hah!” said Frex.

“No hahs at me.” Nanny sniffed. “I’m as entitled to my beliefs as you are, Frexspar the Godly. At least they don’t get me into trouble as yours do.”

Missing Sisters

Missing Sisters Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West

Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West After Alice

After Alice Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister

Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister Son of a Witch

Son of a Witch Matchless

Matchless The Next Queen of Heaven

The Next Queen of Heaven Leaping Beauty: And Other Animal Fairy Tales

Leaping Beauty: And Other Animal Fairy Tales Hiddensee: A Tale of the Once and Future Nutcracker

Hiddensee: A Tale of the Once and Future Nutcracker A Wild Winter Swan

A Wild Winter Swan Egg & Spoon

Egg & Spoon Out of Oz

Out of Oz Leaping Beauty

Leaping Beauty Hiddensee

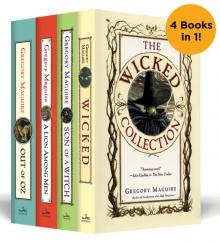

Hiddensee The Wicked Years Complete Collection

The Wicked Years Complete Collection The Next Queen of Heaven: A Novel

The Next Queen of Heaven: A Novel