- Home

- Gregory Maguire

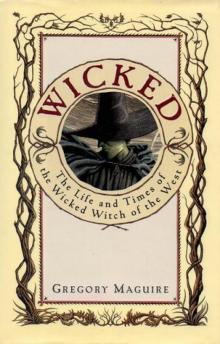

Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West Page 12

Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West Read online

Page 12

“The tree of my dreams is of my dreams, and I don’t speak of that to my friends nor to you, whom I hardly know.”

“Oh, but you know me. We were in a child play set together, you reminded me when we met last year. Why, we’re nearly brother and sister. You can certainly describe your favorite tree to me, and I’ll tell you if I know where she grows.”

“You mock me, Miss Elphie.”

“Well, that I don’t mean to do, Boq.” She used his name without the honorific in a gentle way, as if to underscore her comment about their being like siblings. “I suspect you want to know about Miss Galinda, the Gillikinese girl you met at Madame Morrible’s poetry slaughter last autumn.”

“Perhaps you do know me better than I thought.” He sighed. “Could I hope she thinks of me?”

“Well, you could hope,” said Elphaba. “It would be more efficient to ask her and have done with it. At least you’d know.”

“But you’re a friend of hers, aren’t you? Don’t you know?”

“You don’t want to rely on what I know or not,” said Elphaba, “or what I say I know. I could be lying. I could be in love with you, and betray my roomie by lying about her—”

“She’s your roomie?”

“You’re very surprised at that?”

“Well—no—just—just pleased.”

“The cooks will be wondering what dialogues with the asparagus I’m having now,” Elphaba said. “I could arrange to bring Miss Galinda here some evening if you like. Sooner rather than later, so as to kill your joy the more neatly and entirely. If that is what’s to happen,” she said, “but as I say, how do I know? If I can’t predict what we’ll have for pudding, how can I predict someone’s affections?”

They set a date for three nights hence, and Boq thanked Elphaba fervently, shaking her hand so hard his spectacles jounced on his nose. “You’re a dear old friend, Elphie, even if I haven’t seen you in fifteen years,” he said, giving her back her name without its honorific. She withdrew beneath the boughs of the pear trees and disappeared down the walkway. Boq found his way out of the kitchen garden and back to his room, and reviewed his books again, but the problem wasn’t solved, no, not solved. It was exacerbated. He couldn’t concentrate. He was still awake to hear the noisy clatterings, the hushings, the crashings, and the muttered balladeerings, when the drunken boys returned to Briscoe Hall.

2

Avaric had left for the summer, once the exams were done, and Boq either had flimflammed his way through or disgraced himself, in which case there was little to lose now. This first rendezvous with Galinda might be the last. Boq bothered with his clothes more than usual, and got an opinion on how to fix his hair from the new look in the cafés (a thin white ribbon around the crown of his head, pulling his hair straight from the nub, so that it burst into curls beneath, like froth exploding from an overturned basin of milk). He cleaned his boots several times over. It was too warm for boots but he had no evening slippers. Make do, make do.

On the appointed evening he retraced his way and, on the stable roof, found that a fruit picker’s ladder had been left leaning up against the wall, so he need not descend through the leaves like a vertiginous chimpanzee. He picked his way carefully down the first few rungs, then jumped manfully the rest of the way, avoiding the lettuces this time. On a bench under the wormnut trees sat Elphaba, her knees drawn casually up to her chest and her bare feet flat on the seat of the bench, and Galinda, whose ankles were crossed daintily and who hid behind a satin fan, and who was looking in the other direction anyway.

“Well, my stars and garters, a visitor,” said Elphaba. “Such a surprise.”

“Good evening, ladies,” he said.

“Your head looks like a hedgehog in shock, what did you do to yourself?” said Elphaba. At least Galinda turned to see, but then she disappeared behind the fan again. Could she be so nervous? Could her heart be faint?

“Well I am part Hedgehog, didn’t I tell you?” said Boq. “On my grandfather’s side. He ended up as cutlets for Ozma’s retinue one hunting season, and a tasty memory for all. The recipe is handed down in the family, pasted into the picture album. Served with cheese and walnut sauce. Mmmm.”

“Are you really?” said Elphaba. She put her chin on her knees. “Really Hedgehog?”

“No, it was a fancy. Good evening, Miss Galinda. It was good of you to agree to meet me again.”

“This is highly improper,” said Galinda. “For a number of reasons, as you well know, Master Boq. But my roomie would give me no rest until I said yes. I can’t say that I am pleased to see you again.”

“Oh, say it, say it, maybe it’ll make it true,” said Elphaba. “Try it out. He’s not so bad. For a poor boy.”

“I am pleased that you are so taken with me, Master Boq,” said Miss Galinda, working at courtesy. “I am flattered.” She clearly was not flattered, she was humiliated. “But you must see that there can be no special friendship between us. Apart from the matter of my feelings, there are too many social impediments for us to proceed. I only agreed to come so that I could tell you this in person. It seemed only fair.”

“It seemed only fair and it might be fun, too,” said Elphaba. “That’s why I’m hanging around.”

“There’s the issue of different cultures, to start,” said Galinda. “I know you are a Munchkinlander. I am a Gillikinese. I will need to marry one of my own. It is the only way, I’m sorry”—she lowered her fan and lifted her hand, palm out, to stop his protest—“and furthermore you are a farmer, from the agricultural school, and I require a statesman or a banker from Ozma Towers. This is just how things are. Besides,” said Galinda, “you’re too short.”

“What about his subversion of custom by coming here this way, what about his silliness?” said Elphaba.

“Enough,” said Galinda. “That’ll do, Miss Elphaba.”

“Please, you’re too certain of yourself,” said Boq. “If I may be so bold.”

“You’re not so bold at all,” said Elphaba, “you’re about as bold as tea made from used leaves. You’re embarrassing me with hanging back so. Come on, say something interesting. I’m starting to wish I’d gone to chapel.”

“You’re interrupting,” said Boq. “Miss Elphie, you’ve done a wonderful thing to encourage Miss Galinda to meet me, but I must ask you to leave us alone to sort things out.”

“Neither of you will understand what the other is saying,” said Elphaba calmly. “I’m a Munchkinlander by birth anyway, if not by upbringing, and I’m a girl by accident if not by choice. I’m the natural arbiter between you two. I don’t believe you can get along without me. In fact if I leave the garden you’ll cease to decipher each other’s language entirely. She speaks the tongue of Rich, you speak Clotted Poor. Besides, I paid for this show by wheedling Miss Galinda for three days running. I get to watch.”

“It would be so good of you to stay, Miss Elphaba,” said Galinda, “I require a chaperone when with a boy.”

“See what I mean?” Elphaba said to Boq.

“Then if you must stay, at least let me talk,” Boq said. “Please let me speak, just for a few minutes. Miss Galinda. What you say is true. You are highborn and I am common. You are Gillikinese and I, Munchkinlander. You have a social pattern to conform to, and so do I. And mine doesn’t include marrying a girl too wealthy, too foreign, too expectant. Marriage isn’t what I came here to propose.”

“See, I’m glad I didn’t leave, this is just getting good,” said Elphaba, but clamped her lips shut when they both glared at her.

“I came here to propose that we meet from time to time, that’s all,” said Boq. “That we meet as friends. That, free of expectations, we come to know each other as dear friends. I do not deny that you overwhelm me with your beauty. You are the moon in the season of shadowlight; you are the fruit of the candlewood tree; you are the pfenix in circles of flight—”

“This sounds rehearsed,” said Elphaba.

“You are the mythical sea,”

he concluded, all his eggs in one basket.

“I’m not much for poetry,” said Galinda. “But you’re very kind.” She had seemed to perk up a little at the compliments. Anyway the fan was moving faster. “I don’t really understand the point of friendship, as you call it, Master Boq, between unmarried people of our age. It seems—distracting. I can see it might lead to complications, especially as you confess to an infatuation I cannot hope to return. Not in a million years.”

“It’s the age of daring,” said Boq. “It’s the only time we have. We must live in the present. We are young and alive.”

“I don’t know if alive quite covers it,” said Elphaba. “This sounds scripted to me.”

Galinda rapped Elphaba on the head with her fan, which folded smartly up and opened just as neatly again, an elegant practiced gesture that impressed all of them. “You’re being tiresome, Miss Elphie. I appreciate your company but I didn’t request a running commentary. I’m perfectly capable of deciding the merits of Master Boq’s recital myself. Let me consider his stupid idea. Lurline above, I can hardly hear myself think!”

Losing her temper, Galinda was prettier than ever. So that old saw was true, too. Boq was learning so much about girls! Her fan was dropping. Was that a good sign? If she hadn’t had some affection for him, would she have worn a dress with a neckline that dipped just a tad lower than he had dared hope? And there was the essence of rose water on her. He felt a surge of possibility, an inclination to rub his lips on the place where her shoulder became her neck.

“Your merits,” she was saying. “Well, you’re brave, I suppose, and clever, to have figured this out. If Madame Morrible ever found you here we’d be in severe trouble. Of course you might not know that, so scratch the bravery part. Just clever. You’re clever and you’re sort of, oh, well, I mean to look at—”

“Handsome?” suggested Elphaba. “Dashing?”

“You’re fun to look at,” decided Galinda.

Boq’s face fell. “Fun?” he said.

“I’d give a lot to achieve fun,” Elphaba said. “The best I usually hope for is stirring, and when people say that they’re usually referring to digestion—”

“Well, I might be all or none of the things you say,” said Boq staunchly, “but you will learn that I am persistent. I will not let you say no to our friendship, Galinda. It means too much to me.”

“Behold the male beast roaring in the jungle for his mate,” said Elphaba. “See how the female beast giggles behind a shrub while she organizes her face to say, Pardon dear, did you say something?”

“Elphaba!” they both cried at her.

“My word, duckie!” said a voice behind them, and all three turned. It was some middle-aged minder in a striped apron, her thinning gray hair twisted in a knot on her head. “What are you getting yourself up to?”

“Ama Clutch!” Galinda said. “How did you think to look for me here?”

“That Tsebra cook told me some yacky-yacky was going on out here. You think they’re blind in there? Now who is this? This don’t look good at all, not to me.”

Boq stood. “I am Master Boq of Rush Margins, Munchkinland. I am nearly a third-year fellow at Briscoe Hall.”

Elphaba yawned. “Is this show over?”

“Well, I am shocked! A guest don’t get shown into the vegetable garden, so I guess you arrived uninvited! Sir, get yourself gone from here before I be calling the porters to remove you!”

“Oh, Ama Clutch, don’t make a scene,” said Galinda, sighing.

“He’s hardly developed enough to worry about,” pointed out Elphaba. “Look, he’s still beardless. And from that we can deduce—”

Boq said in a rush, “Perhaps this is all wrong. I did not come here to be abused. Forgive me, Miss Galinda, if I have failed even to amuse you. As for you, Miss Elphaba”—his voice was as cold as he could make it, and that was colder than he’d ever heard it himself—“I was wrong to have trusted in your compassion.”

“Wait and see,” said Elphaba. “Wrong takes an awful long time to be proven, in my experience. Meanwhile, why don’t you come back sometime?”

“There is no second time to this,” said Ama Clutch, tugging at Galinda, who was proving as sedentary as set cement. “Miss Elphaba, shame on you for encouraging this scandal.”

“Nothing here has been perpetrated but badinage, and bad badinage at that,” said Elphaba. “Miss Galinda, you’re mighty stubborn there. You’re planting yourself in the vegetable garden for good in the hopes that this Boy Visitation might occur again? Have we misread your interest?”

Galinda stood at last with some dignity. “My dear Master Boq,” she said, as if dictating, “it was ever my intention to dissuade you from pursuing me, in romantic attachment or even in friendship, as you put it. I had not meant to bruise you. It is not in my nature.” At this Elphaba rolled her eyes, but for once kept her mouth shut, perhaps because Ama Clutch had dug her fingernails into Elphaba’s elbow. “I will not deign to arrange another meeting like this. As Ama Clutch reminds me, it is beneath me.” Ama Clutch hadn’t exactly said that, but even so, she nodded grimly. “But if our paths cross in a legitimate way, Master Boq, I will do you the courtesy at least of not ignoring you. I trust you will be satisfied with that.”

“Never,” said Boq with a smile, “but it’s a start.”

“And now good evening,” said Ama Clutch on behalf of them all, and steered the girls away. “Fresh dreams, Master Boq, and don’t come back!”

“Miss Elphie, you were horrible,” he heard Galinda say, while Elphaba twisted around and waved good-bye with a grin he could not clearly read.

3

So the summer began. Since he passed the exams, Boq was free to plan one last year at Briscoe Hall. Daily he hied himself over to the library at Three Queens, where under the watchful eye of a titanic Rhinoceros, the head archival librarian, he sat cleaning old manuscripts that clearly weren’t looked at more than once a century. When the Rhino was out of the room, he had flighty conversations with the two boys on either side of him, classic Queens boys, full of gibbering gossip and arcane references, teasing and loyal. He enjoyed them when they were in good spirits, and he detested their sulks. Crope and Tibbett. Tibbett and Crope. Boq pretended confusion when they got too arch or suggestive, which seemed to happen about once a week, but they backed off quickly. In the afternoons they would all take their cheese sandwiches by the banks of the Suicide Canal and watch the swans. The strong boys at crew, coursing up and down the canal for summer practice, made Crope and Tibbett swoon and fall on their faces in the grass. Boq laughed at them, not unkindly, and waited for fate to deliver Galinda back into his path.

It wasn’t too long a wait. About three weeks after their vegetable garden liaison, on a windy summer morning, a small earthquake caused some minor damage in the Three Queens library, and the building had to be closed for some patching. Tibbett, Crope, and Boq took their sandwiches, with some beakers of tea from the buttery, and they flopped down at their favorite place on the grassy banks of the canal. Fifteen minutes later, along came Ama Clutch with Galinda and two other girls.

“I do believe we know you,” said Ama Clutch as Galinda stood demurely a step behind. In cases such as these it was the servant’s duty to elicit names from the strangers in the group, so that they might greet each other personally. Ama Clutch registered out loud that they were Masters Boq, Crope, and Tibbett, meeting Misses Galinda, Shenshen, and Pfannee. Then Ama Clutch moved a few feet away to allow the young people to address one another.

Boq leaped up and gave a small bow, and Galinda said, “As in line with my promise, Master Boq, may I enquire how you’re keeping?”

“Very well, thank you,” said Boq.

“He’s ripe as a peach,” said Tibbett.

“He’s downright luscious, from this angle,” said Crope, sitting a few steps behind, but Boq turned and glared so fiercely that Crope and Tibbett were chastened, and fell into a mock sulk.

“And you

, Miss Galinda?” continued Boq, searching her well-

composed face. “You are well? How thrilling to see you in Shiz for the summer.” But that wasn’t the right thing to say. The better girls went home for the summer, and Galinda as a Gillikinese must feel it deeply that she was stuck here, like a Munchkinlander or a commoner! The fan came up. The eyes went down. The Misses Shenshen and Pfannee touched her shoulders in mute sympathy. But Galinda sallied on.

“My dear friends the Misses Pfannee and Shenshen are taking a house for the month of Highsummer on the shores of Lake Chorge. A little fantasy house near the village of Neverdale. I’ve decided to make my holiday there instead of taking that tiresome trek back to the Pertha Hills.”

“How refreshing.” He saw the beveled edges of her lacquered fingernails, the moth-colored eyelashes, the glazed and buffed softness of cheek, the sensitive tuck of skin just at the cleft of her upper lip. In the summer morning light, she was dangerously, inebriatingly magnified.

“Steady,” said Crope, and he and Tibbett jumped up and they each caught Boq by an elbow. He then remembered to breathe. He couldn’t think of anything else to say though, and Ama Clutch was turning her handbag around and around in her hands.

“So we’ve got jobs,” said Tibbett, to the rescue. “The Three Queens library. We’re housekeeping the literature. We’re the cleaning maids of culture. Are you working, Miss Galinda?”

“I should think not,” said Galinda. “I need a rest from my studies. It has been a harrowing year, harrowing. My eyes are still tired from reading.”

“How about you girls?” said Crope, outrageously casual. But they only giggled and demurred and inched away. This was their friend’s encounter, not theirs. Boq, regaining his composure, could feel the group beginning to shift itself into motion again. “And Miss Elphie?” he enquired, to hold them there. “How is your roomie?”

“Headstrong and difficult,” said Galinda severely, for the first time speaking in a normal voice, not the faint social whisper. “But, thank Lurline, she’s got a job, so I get some relief. She’s working in the lab and the library under our Doctor Dillamond. Do you know of him?”

Missing Sisters

Missing Sisters Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West

Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West After Alice

After Alice Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister

Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister Son of a Witch

Son of a Witch Matchless

Matchless The Next Queen of Heaven

The Next Queen of Heaven Leaping Beauty: And Other Animal Fairy Tales

Leaping Beauty: And Other Animal Fairy Tales Hiddensee: A Tale of the Once and Future Nutcracker

Hiddensee: A Tale of the Once and Future Nutcracker A Wild Winter Swan

A Wild Winter Swan Egg & Spoon

Egg & Spoon Out of Oz

Out of Oz Leaping Beauty

Leaping Beauty Hiddensee

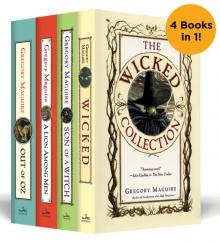

Hiddensee The Wicked Years Complete Collection

The Wicked Years Complete Collection The Next Queen of Heaven: A Novel

The Next Queen of Heaven: A Novel