- Home

- Gregory Maguire

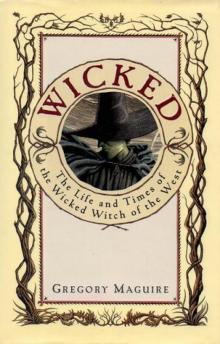

Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West Page 13

Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West Read online

Page 13

“Doctor Dillamond? Do I know of him?” said Boq. “He’s the most impressive biology tutor in Shiz.”

“By the by,” said Galinda, “he’s a Goat.”

“Yes, yes. I wish he would teach us. Even our professors acknowledge his prominence. Apparently, years ago, back in the reign of the Regent, and before, he used to be invited annually to lecture at Briscoe Hall. But the restrictions changed even that, so I’ve never really met him. Just to see him at that poetry evening, last year, so briefly, was a treat—”

“Well he does go on,” said Galinda. “Brilliant he may be, but he has no sense of when he’s become tedious. Anyway, Miss Elphie’s hard at work, doing something or other. She will go on about it, too. I think it’s contagious!”

“Well, a lab, it breeds things,” said Crope.

“Yes,” said Tibbett, “and incidentally may I add that you’re every bit as lovely as Boq gushes you are. We’d put it down to an overactive imagination born of affectional and physical frustration—”

“You know,” said Boq, “between your Miss Elphie and my erstwhile friends here, we have no real hope of friendship at all. Shall we organize a duel and kill each other instead? Count off ten paces, turn and shoot? It would save so much bother.”

But Galinda didn’t approve of such joking. She nodded in a dismissive way, and the group of females moved out along the graveled path, following the curve of the canal. Miss Shenshen was heard to say in a deep, breathy voice, “Oh, my dear, he is sweet, in a toylike way.”

The voice faded out, Boq turned to rail at Crope and Tibbett, but they fell to tickling him and they all collapsed in a heap on the remains of their lunch. And since there was no hope in changing them, Boq abandoned the impulse to correct his friends. Really, what difference did their callow banter make if Miss Galinda found him so impossible?

A week or two later, on his afternoon off, Boq took himself in to Railway Square. He lingered at a kiosk, staring. Cigarettes, ersatz love charms, naughty drawings of women undressing, and scrolls painted with lurid sunsets, overladen with one-line inspirational slogans. “Lurline Lives on Within Each Heart.” “Safe Keep the Wizard’s Laws, and the Wizard’s Laws Will Keep You Safe.” “I Pray to the Unnamed God That Justice Will Walk Abroad in Oz.” Boq noted the variety: the pagan, the authoritarian, and the old-fashioned unionist impulses.

But nothing directly sympathetic to the royalists, who had gone underground in the sixteen harsh years since the Wizard had first wrested power from the Ozma Regent. The Ozma line had been Gillikinese originally, and surely there were active pockets of resistance to the Wizard? But Gillikin had, in fact, thrived under the Wizard, so the royalists kept mum. Besides, everyone had heard the rumors of strict court action against turncoats and peristrophists.

Boq bought a broadsheet published out of the Emerald City—several weeks old, but it was the first he’d seen in some time—and he settled down at a café. He read about the Emerald City Home Guard suppressing some Animal dissenters, who were making a nuisance of themselves in the palace gardens. He looked for news of the provinces, and found a filler about Munchkinland, which continued experiencing near-drought conditions; occasional thunderbursts would drench the ground, but the water would run off or sink uselessly into the clay. They said that hidden subterranean lakes underlay the Vinkus region, that water resources there could serve the whole of Oz. But the idea of a canal system across the entire country made everyone laugh. The expense! There was great disagreement between the Eminences and the Emerald City as to what was to be done.

Secession, thought Boq seditiously, and looked up to see Elphaba, alone, without even a nanny or Ama, standing over him.

“What a delicious expression you have on your face, Boq,” she said. “It’s much more interesting than love.”

“It is love, in a way,” said Boq, then remembered himself, and leaped to his feet. “Won’t you join me? Please, take a seat. Unless you’re worried about being unchaperoned.”

She sat down, looking a bit etiolated, and allowed him to call for a cup of mineral tea. She had a parcel in brown paper and string under her arm. “A few trinkets for my sister,” she said. “She’s like Miss Galinda, she loves the fancy outside of things. I found a Vinkus shawl in the bazaar, red roses on a black background, with black and green fringe. I’m sending it to her, and a pair of striped stockings that Ama Clutch knitted for me.”

“I didn’t know you had a sister,” he said. “Was she in the play group we were in together?”

“She’s three years younger,” Elphaba said. “She’ll come to Crage Hall before long.”

“Is she as difficult as you are?”

“She’s difficult in a different way. She’s crippled, pretty severely, is my Nessarose, so she’s a handful. Even Madame Morrible doesn’t quite know the extent of it. But by then I’ll be a third-year girl and will have the nerve to stand up to the Head, I guess. If anything gives me nerve, it’s people making life hard for Nessarose. Life is already hard enough for her.”

“Is your mama raising her?”

“My mother is dead. My father is in charge, nominally.”

“Nominally?”

“He’s religious,” said Elphaba, and made the circling palms gesture that indicated you could grind millstone against millstone all you liked, but there wasn’t any quern in the land that could produce flour if there was no grain to grind.

“It sounds very hard for you all. How did your mama die?”

“She died in childbirth, and this is the end of the personal interview.”

“Tell me about Doctor Dillamond. I hear you’re working for him.”

“Tell me about your amusing campaign for the heart of Galinda the Ice Queen.”

Boq really wanted to hear about Doctor Dillamond, but was derailed by Elphaba’s remark. “I will keep on, Elphie, I will! When I see her I’m so smitten with longing, it’s like fire in my veins. I can’t speak, and the things I think about are like visions. It’s like dreaming. It’s like floating in your dreams.”

“I don’t dream.”

“Tell me, is there any hope? What does she say? Does she ever even imagine that her feelings for me might change?”

Elphaba sat with her two elbows on the table, her hands clasped in front of her face, her two forefingers leaning against each other and against her thin, grayish lips. “You know, Boq,” she said, “the thing is I have become fond of Galinda myself. Behind her starry-eyed love of herself there is a mind struggling to work. She does think about things. When her mind is really working, she could, if led, think on you—even, I suspect, somewhat fondly. I suspect. I don’t know. But when she slides back into herself, I mean into the girl who spends two hours a day curling that beautiful hair, it’s as if the thinking Galinda goes into some internal closet and shuts the door. Or as if she’s in hysterical retreat from things that are too big for her. I love her both ways, but I find it odd. I wouldn’t mind leaving myself behind if I could, but I don’t know the way out.”

“I propose you’re being hard on her, and you’re certainly too forward,” said Boq sternly. “Were she sitting here I think she’d be astounded to hear you speak so freely.”

“I’m just trying to behave as I think a friend should behave. Granted, I haven’t had much practice.”

“Well, I question your friendship with me, if you consider Miss Galinda your friend too, and if that’s how you tear a friend apart in her absence.”

Though Boq was irritated, he found that this was a more lively discussion than the conventional patter he and Galinda had so far exchanged. He didn’t want to burn Elphaba off with criticism. “I’m ordering you another mineral tea,” he said, in an authoritative voice, his father’s voice in fact, “and then you can tell me about Doctor Dillamond.”

“Skip the tea, I’m still nursing this one and you have no more money than I do, I bet,” said Elphaba, “but I’ll tell you about Doctor Dillamond. Unless you are too affronted at the slice and ang

le of my opinions.”

“Please, perhaps I am wrong,” said Boq. “Look, it’s a nice day, we’re both off the campus. How do you come to be out alone, by the way? Is your escape sanctioned by Madame Morrible?”

“Take a guess about that,” she said, grinning. “Once it was clear that you could come and go from Crage Hall by way of the vegetable garden and the roof of the adjacent stable, I decided I could too. I’m never missed.”

“That’s hard for me to believe,” said he, daringly, “for you’re not the kind who blends into the woodwork. Now tell me about Doctor Dillamond. He’s my idol.”

She sighed, and set the package down on the table at last, and settled in for a long chat. She told him about Doctor Dillamond’s work in natural essences, trying to determine by scientific method what the real differences were between animal and Animal tissue, and between Animal and human tissue. The literature on the matter, she had learned from doing the legwork herself, was all couched in unionist terms, and pagan terms before that, and they didn’t hold up to scientific scrutiny. “Don’t forget Shiz University was originally a unionist monastery,” said Elphaba, “so despite the anything-goes attitude among the educated elite, there are still bedrocks of unionist bias.”

“But I’m a unionist,” said Boq, “and I don’t see the conflict. The Unnamed God is accommodating to many ranges of being, not just human. Are you talking about a subtle bias against Animals, interwoven into early unionist tracts, and still in operation today?”

“That’s certainly what Doctor Dillamond thinks. And he’s a unionist himself. Explain that paradox and I’d be glad to convert. I admire the Goat intensely. But the real interest of it to me is the political slant. If he can isolate some bit of the biological architecture to prove that there isn’t any difference, deep down in the invisible pockets of human and Animal flesh—that there’s no difference between us—or even among us, if you take in animal flesh too—well, you see the implications.”

“No,” said Boq, “I don’t think I do.”

“How can the Banns on Animal Mobility be upheld if Doctor Dillamond can prove, scientifically, that there isn’t any inherent difference between humans and Animals?”

“Oh, now that’s a blueprint for an impossibly rosy future,” said Boq.

“Think about it,” said Elphaba. “Think, Boq. On what grounds could the Wizard possibly continue to publish those Banns?”

“How could he be persuaded not to? The Wizard has dissolved the Hall of Approval indefinitely. I don’t believe, Elphie, that the Wizard is open to entertaining arguments, even by as august an Animal as Doctor Dillamond.”

“But of course he must be. He’s a man in power, it’s his job to consider changes in knowledge. When Doctor Dillamond has his proof, he’ll write to the Wizard and begin to lobby for change. No doubt he’ll do his best to let Animals the land over know what he’s intending, too. He isn’t a fool.”

“Well I didn’t say he was a fool,” said Boq. “But how close do you think he is to getting firm evidence?”

“I am a student handmaid,” said Elphaba. “I don’t even understand what he means. I’m only a secretary, an amanuensis—you know he can’t write things himself, he can’t manage a pen with his hoofs. I take dictation and I file and I dash to the Crage Hall library and look things up.”

“Briscoe Hall library would be a better place to hunt for that kind of material,” said Boq. “Even Three Queens, where I work this summer, has stacks of documents from the monks’ observations of animal and vegetable life.”

“I know I am not traditionally presented,” said Elphaba, “but I believe on the grounds of being a girl I am excluded from the Briscoe Hall library. And on the grounds of being an Animal so too, now at least, is Doctor Dillamond. So those valuable resources are off limits to us.”

“Well,” said Boq carelessly, “if you knew exactly what you wanted . . .

I have access to the stacks in both collections.”

“And when the good Doctor is finished ferreting out the difference between Animals and people, I will propose he apply the same arguments to the differences between the sexes,” said Elphaba. Then she registered what Boq had said, and stretched out her hand, almost as if to touch him. “Oh Boq. Boq. On behalf of Doctor Dillamond, I accept your generous offer of help. I’ll get the first list of sources to you within the week. Just leave my name out of it. I don’t care so much about incurring Horrible Morrible’s wrath against myself, but I don’t want her taking out her annoyance on my sister, Nessarose.”

She downed the last of her tea, gathered her parcel, and had sprung up almost before Boq could pull himself to his feet. Various customers, lingering over their elevenses with their own broadsheets or novellas, looked up at the ungainly girl pushing out the doors. As Boq settled back down, hardly yet registering what he had gotten himself into, he realized, slowly but thoroughly, that this morning there were no Animals taking their morning tea in here. No Animals at all.

4

In years to come—and Boq would live a long life—he would remember the rest of the summer as scented with the must of old books, when ancient script swam before his eyes. He sleuthed alone in the musty stacks, he hovered over the mahogany drawers lined with vellum manuscripts. All season long, it seemed, the lozenge-paned windows between bluestone mullions and transoms misted over again and again with flecks of small but steady rain, almost as brittle and pesky as sand. Apparently the rain never made it as far as Munchkinland—but Boq tried not to think about that.

Crope and Tibbett were coerced into researching for Doctor Dillamond, too. At first they had to be dissuaded from going about their forays in costumes of disguise—fake pince-nez, powdered wigs, cloaks with high collars, all to be found in the well-stocked locker of the Three Queens Student Theatrical and Terpsichorean Society. But when convinced of the seriousness of the mission, they fell to with gusto. Once a week they met Boq and Elphaba in the café in Railway Square. Elphaba showed up, during these misty weeks, entirely swathed in a brown cloak with a hood and veil that hid all but her eyes. She wore long, frayed gray gloves that she boasted buying secondhand from a local undertaker, cheap for having been used in funeral services. She sheathed her bamboo-pole legs in a double thickness of cotton stocking. The first time Boq saw Elphaba like this, he said, “I just barely manage to convince Crope and Tibbett to lose the espionage drag, and you come in looking like the original Kumbric Witch.”

“I don’t dress for your approval, boys,” she said, shucking her cloak and folding it inside out so that the wet wool never touched her. On the occasion when another café patron would come through, shaking water off an umbrella, Elphaba always recoiled, flinching if she was caught by even a scattering of drops.

“Is that religious conviction, Elphie, that you keep yourself so dry?” said Boq.

“I’ve told you before, I don’t comprehend religion, although conviction is a concept I’m beginning to get. In any case, someone with a real religious conviction is, I propose, a religious convict, and deserves locking up.”

“Hence,” observed Crope, “your aversion to all water. Without your knowing it, it might be a baptismal splash, and then your liberty as a free-range agnostic would be curtailed.”

“I thought you were too self-absorbed to notice my spiritual pathology,” said Elphaba. “Now, boys, what’ve we got today?”

Every time, Boq thought: Would that Galinda were here. For the casual camaraderie that grew up among them during these weeks was so refreshing—a model of ease and even wit. Against convention they had dropped the honorifics. They interrupted one another and laughed and felt bold and important because of the secrecy of their mission. Crope and Tibbett cared little about Animals or the Banns—they were both Emerald City boys, sons, respectively, of a tax collector and of a palace security advisor—but Elphaba’s passionate belief in the work enlivened them. Boq himself grew more involved, too. He imagined Galinda drawing her chair up with them, losing her upper-c

rust reserve, allowing her eyes to glow with a shared and secret purpose.

“I thought I knew all the shapes of passion,” Elphaba said one bright afternoon. “I mean, growing up with a unionist minister for a father. You come to expect that theology is the fundament on which all other thought and belief is based. But boys!—this week, Doctor Dillamond made some sort of a scientific breakthrough. I’m not sure what it was, but it involved manipulating lenses, a pair of them, so he could peer at bits of tissue that he had laid on a transparent glass and backlit by candlelight. He began to dictate, and he was so excited that he sang his findings; he composed arias out of what he was seeing! Recitatives about structure, about color, about the basic shapes of organic life. He has a horrible sandpapery voice, as you might imagine for a Goat; but how he warbled! Tremolo on the annotations, vibrato on the interpretations, and sostenuto on the implications: long, triumphant open vowels of discovery! I was sure someone would hear. I sang with him, I read his notes back to him like a student of musical composition.”

The good Doctor was emboldened by his findings, and he required that their digging become more and more focused. He did not want to announce any breakthroughs until he had figured out the most politically advantageous way to present them. Toward the end of the summer the push was on to find Lurlinist and early unionist disquisitions on how the Animals and the animals had been created and differentiated. “It’s not a matter of uncovering a scientific theory by a prescientific company of unionist monks or pagan priests and priestesses,” explained Elphaba. “But Doctor Dillamond wants to authenticate the way our ancestors thought about this. The Wizard’s right to impose unjust laws may be better challenged if we know how the old codgers explained it to themselves.”

It was an interesting exercise.

Missing Sisters

Missing Sisters Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West

Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West After Alice

After Alice Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister

Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister Son of a Witch

Son of a Witch Matchless

Matchless The Next Queen of Heaven

The Next Queen of Heaven Leaping Beauty: And Other Animal Fairy Tales

Leaping Beauty: And Other Animal Fairy Tales Hiddensee: A Tale of the Once and Future Nutcracker

Hiddensee: A Tale of the Once and Future Nutcracker A Wild Winter Swan

A Wild Winter Swan Egg & Spoon

Egg & Spoon Out of Oz

Out of Oz Leaping Beauty

Leaping Beauty Hiddensee

Hiddensee The Wicked Years Complete Collection

The Wicked Years Complete Collection The Next Queen of Heaven: A Novel

The Next Queen of Heaven: A Novel